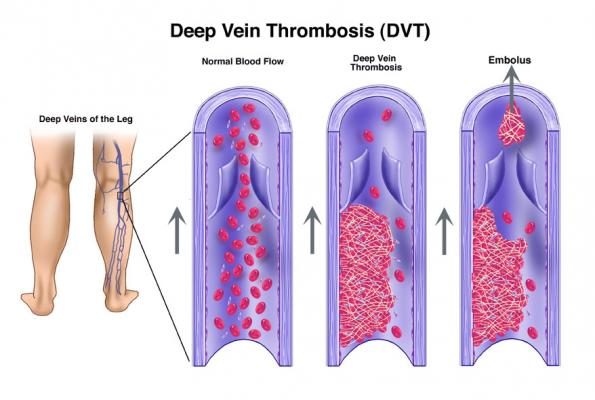

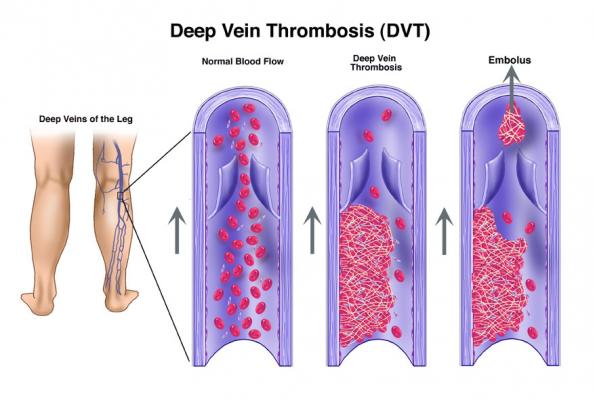

During plastic surgery, one of the biggest concerns patients and their surgeon’s have is the potential for the development of blood clots in the patient’s legs. These are referred to as a DVT or Deep Vein Thrombosis. The pathophysiology, or the reason these clots develop, has to do with three possible factors. 1) Stasis, or lack of movement of blood in the legs during surgery, 2) Hypercoagulability, increased clotting in the blood which could be due to genetic disorders, or 3) Injury to the blood vessels themselves.

Under normal circumstances, when a patient is not under anesthesia, their calf muscles act as a pump to keep blood moving. But during general anesthesia, the “calf pump” doesn’t function to the same degree. So blood pools in the deep veins of the leg, leading to an increased risk of the blood developing into a blood clot. By itself, the development of the clot isn’t deadly. But that clot could subsequently travel to the heart and lungs in what’s referred to as a pulmonary embolism. A “small” pulmonary embolism (ie a small clot traveling to the heart/lungs), could lead to mild shortness of breath that passes with time. On the other end of the spectrum, a pulmonary embolism consisting of a large clot could lead to sudden death. This is why DVT’s and pulmonary embolisms are of such great concern for the surgeon and their patient.

How do you reduce DVT’s in surgery?

This is a controversial question. For almost two decades, one option was to give patients chemoprophylaxis, or medications like blood thinners, to reduce the risk of forming a DVT in the leg. However, these medications are not without risks. In an amazing book chapter on the subject by Dr. Eric Swanson, he explains why blood thinners aren’t the answer. The annual risk of an adult having a DVT is 0.1-0.3%. But the risk of having a major bleeding complication (hematoma) from a blood thinner is 3% annually. So the risk of having a hematoma is higher than the risk of having a DVT.

You might think, well if it reduces my risk of a DVT to any extent during surgery, maybe it’s worth the risk? Despite conventional wisdom, there’s very little evidence that these blood thinners actually reduce the risk of DVT during surgery. So do you just accept the risk of a DVT by avoiding blood thinners because you don’t want a hematoma?

The alternative to blood thinners

Luckily there are alternative methods to reduce your risk of a DVT and ultimately, pulmonary embolisms. Dr. Swanson describes SAFE anesthesia. This is an acronym for Spontaneous breathing, Avoid inhalation gases, Face up and Extremities mobile.

Spontaneous breathing – avoidance of paralyzing the patient during surgery with medications called paralytics. If paralyzed during surgery, the patient is dependent on the ventilator to breathe. Paralyzing a patient for general anesthesia can also reduce blood pressure. If the anesthesiologist avoids paralytics, then the patient can spontaneously breathe on their own, blood pressure doesn’t drop and the calf muscle pump continues to work, thereby reducing stasis and DVT formation.

Avoid inhalation gases – think stronger versions of laughing gas. By using propofol (yes, the Michael Jackson drug) instead of gas to keep the patient asleep, the risk of DVT is lower.

Face up when possible, meaning keeping the patient on their back with their face up. This is obviously difficult in situations where the surgeon needs to operate on the patients back wherein they’re laying face down. But switching the patient from side to side, to always avoid being face down is one option.

Extremities mobile. Moving the limbs at some point during surgery, either by turning the patient, or repeated checking of limb position, can reduce stasis and DVT’s forming.

Checking for DVT’s preoperatively

Many offices, including ours, utilizes Doppler ultrasound surveillance to determine if someone has a deep venous thromboses before surgery. By knowing the patient doesn’t have a DVT ahead of time, they’re that much safer going into surgery.

What about those squeezers?!

SCDs (sequential compression devices) are the “squeezers” doctors use to reduce DVT formation in the legs. Some patients even rent or purchase these machines after surgery for home use. All in an effort to reduce the formation of a DVT and thereby a pulmonary embolus.

In truth, there is no evidence that sequential compression devices affect the frequency of deep venous thromboses in plastic surgery patients.

It may not be profound, and certainly not technically advanced, but the best way to avoid DVTs after surgery is to get up and walk around. In our office, we recommend showering hours after the procedure to force the patient to get up out of bed and take a walk to the bathroom.

Concerned about too much activity? Our mantra is, “If it hurts, stop doing it. If it doesn’t hurt, you can do it!” Listen to your body so you don’t overdo it. Don’t push through the pain. But stay out of bed as much as possible and get back to regular activity. The muscles in the calves were designed to reduce the risk of blood clots. So let them do their job but getting up and walking around rather than depending on devices like SCDs that are not proven to work.