If you’re considering a breast augmentation, then you’ve no doubt heard about two potential medical issues. One is Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma, or ALCL, and the other is Breast Implant Associated Illness, or BIAI. ALCL, which you can read about here, is a more limited issue that has affected a total of 733 people globally. To be clear, that 733 figure is not this year. That’s the total number of ALCL cases ever. BIAI has affected more women, based on the size of their representative Facebook groups, but it’s a much harder ailment to diagnose.

If you’re considering a breast augmentation, then you’ve no doubt heard about two potential medical issues. One is Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma, or ALCL, and the other is Breast Implant Associated Illness, or BIAI. ALCL, which you can read about here, is a more limited issue that has affected a total of 733 people globally. To be clear, that 733 figure is not this year. That’s the total number of ALCL cases ever. BIAI has affected more women, based on the size of their representative Facebook groups, but it’s a much harder ailment to diagnose.

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) vs Breast implant associated illness (BIAI)

Compared to BIAI, it’s “easier” to determine if someone has ALCL. They’ll present with a late onset fluid collection or seroma around their breast implants (most typically textured implants), 1 to 20 years after surgery. And when sent to the lab, that fluid collection will test positive for the CD30 protein or negative for the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) protein. ALCL is treatable, and cure is possible, with removal of the implant and surrounding scar tissue when performed early. Again, the most encouraging aspect of ALCL is that it is diagnosable and treatable.

While BIAI and ALCL are similar in that they both seem to affect patients with textured implants, they are very different in other ways. For example, BIAI has many vague symptoms also associated with other disease processes, including those not involving breast implants. Symptoms that women commonly report are fatigue, anxiety, foggy thinking, memory loss, headaches, muscle pains and even hair loss and skin rashes. A caring sympathetic doctor would not dispute that a patient is feeling these symptoms. But this is not enough to make the diagnosis of BIAI.

BIAI is difficult to diagnose for two reasons. First, there’s not always a physical symptom like seroma formation. And secondly, there’s currently no diagnostic lab test, as in the case of ALCL. However, in an exceptional case, I had a patient with BIAI that actually had physical symptoms and a positive lab test. But a word of caution. The lab tests referenced here are not specific to BIAI and are certainly not diagnostic of BIAI in the same way CD30 is diagnostic of a symptomatic patient with ALCL.

A BIAI patient with symptoms and lab abnormalities

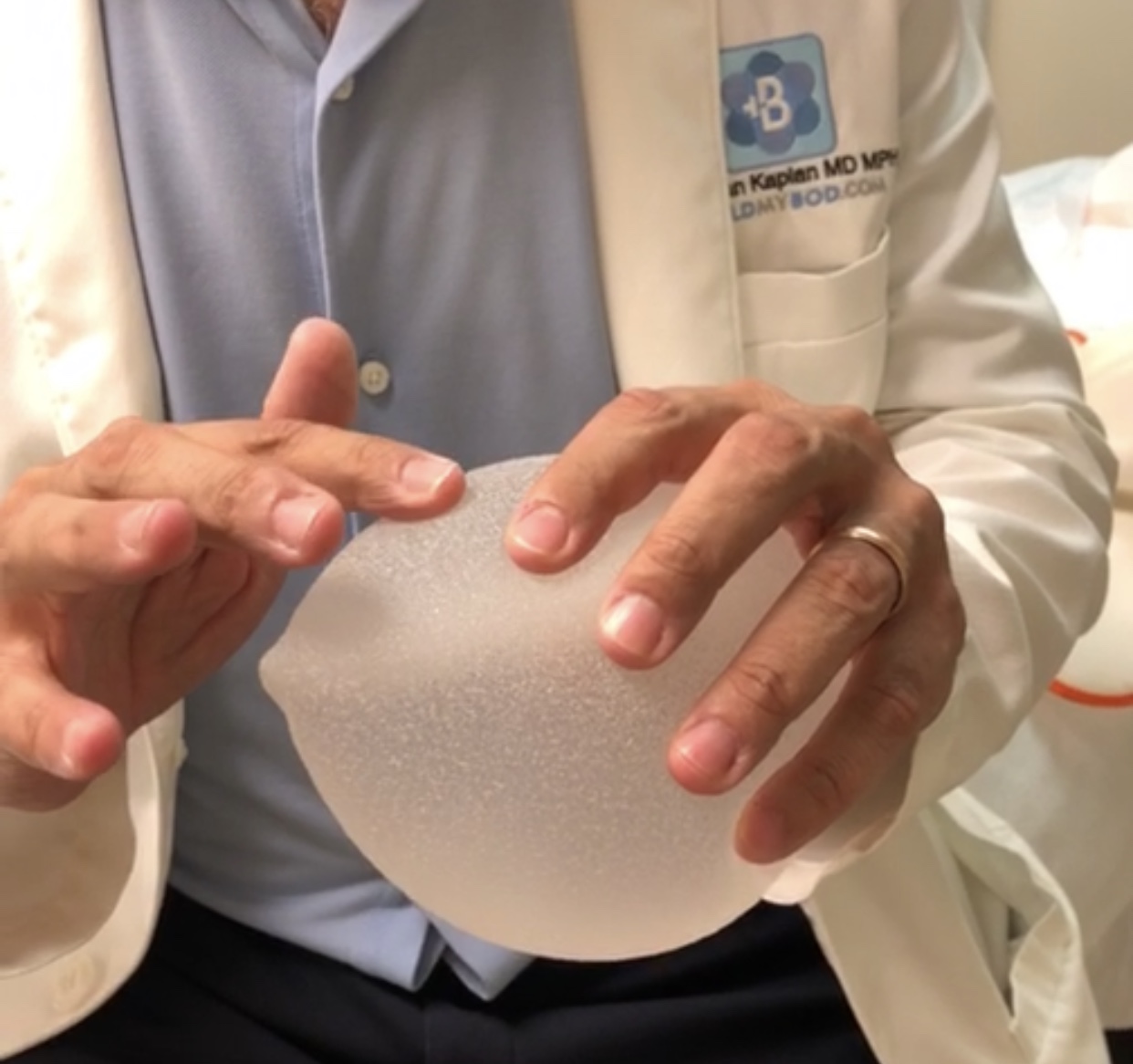

A previously healthy, thin, fit, female patient of mine had breast augmentation with 320cc round-base, shaped, textured implants in April of 2016. Approximately 6 months after surgery, she started to experience rashes (see photo), extremely high blood pressure (168/110) and numerous food allergies (gluten, dairy, alcohol, coffee) which would lead to more rashes.

Her hands would turn white and purple, a sign of Raynaud’s disease (see photo) – changes she never experienced prior to breast augmentation. Soon after, she started to experience muscle weakness and a sensation that her legs were very heavy. Upon going to the ER, her lab tests showed very high levels of creatine kinase (CK). This is an enzymatic protein found in the heart, brain, skeletal muscle, and other tissues. It is released into the bloodstream when there is damage to those tissues. Measuring high levels of CK is a common test for someone actively experiencing a heart attack. CK levels are high when there is damage to the heart muscle because coronary arteries are clogged and the heart isn’t receiving enough oxygen.

Despite a high CK level, there was no reason to suspect she was having a heart attack. She was young, had no chest pain and no changes on EKG. But they were concerned that elevated CK levels, whatever their cause, could damage the kidneys, as is possible in rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdo, for short, is the rapid breakdown of muscle tissue and release of proteins into the bloodstream. The large amount of proteins can damage the kidneys and cause acute renal failure.

While the doctors had not yet diagnosed the cause of the elevated CK protein in the blood, they worried about its effect on the kidneys. In an overabundance of caution, she remained in the hospital for 3 nights with IV fluids to help flush out the CK protein before it could damage the kidneys, which was successful.

Unsure of the cause of her full body symptoms, she dramatically shifted her lifestyle. This included alcohol cessation, which she already used in moderation beforehand, and avoidance of foods that could cause any bodily inflammation.

After another admission to the hospital in July of 2019 (3 years after surgery) because of weakness, muscle wasting and an elevated creatine kinase level of 411 U/L (normal is 24-173 U/L), she decided the implants were the underlying cause of these symptoms and made the decision to remove them.

In November of 2019 (3+ years after implantation), I removed the implants and the surrounding scar tissue (capsulectomy). Since then, her rashes, Raynaud’s and all other symptoms have disappeared. As of January 2020, 2 months after implant removal, her creatine kinase level returned to the normal range.

So what does it all mean?

This represents one of the few examples in the literature when demonstrable physical symptoms (rash and Raynaud’s disease) in combination with a lab test, both had resolution after removal of implants. And while resolution of elevated lab tests and symptoms should be seen as a success after implant removal in patients experiencing BIAI, the true success remains elusive.

What we need is a preoperative antigen test that can predict, with a high degree of certainty, that if someone gets implants, their body may react to the implants and enter a sustained, chronic phase of inflammation. And if the patient is found to be “reactive” to such a test, they wouldn’t get implants.

Testing like this is not unheard of within aesthetic medicine. For example, one component of the dermal filler Bellafill is bovine collagen. Because some patients can have a reaction to bovine collagen, they receive a skin test one month before Bellafill treatment. If they have a skin reaction, they are not a candidate for this long-lasting dermal filler. Similarly, if someone would have a reaction to some future “breast implant antigen” test, they would not be a candidate for breast augmentation.

Conclusion

For those who believe no one should get breast augmentation until the development of such a test, that is an unreasonable approach. There are millions of women around the world who currently have breast implants and over 400,000 undergoing the procedure for cosmetic or reconstructive reasons each year. And with a relatively small percentage experiencing ALCL or BIAI, the benefits of breast augmentation greatly outweighs the risks. While continuing to provide this service to women for cosmetic reasons or for reconstruction after mastectomy, we should also continue to develop prognostic techniques to avoid augmentation in the few patients that will have very real adverse reactions.

And for those few patients that do have symptoms after implantation, luckily there’s treatment. They can be potentially cured with explantation (implant removal) and capsulectomy.

Dr. Jonathan Kaplan is a board-certified plastic surgeon based in San Francisco, CA and founder/CEO of BuildMyBod Health, a price transparency-lead generation platform. You can watch him operate and educate @realdrbae on Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok.